Why do our coins have milled or engraved edges? The original purpose was to identify whether or not a coin had been ‘clipped’, and the weight — and consequently the value — reduced. In the seventeenth century coins were of gold or silver, both comparatively soft metals, and the edges could easily be trimmed, losing as much as 50% of the value in the case of gold. The clippings could be melted down and sold. Because of this the effect on Britain’s economy reached such a pitch at the end of the century that the government of the day decided to issue new silver coinage with a value still based on weight, but it needed to find a way of compensating for the shortfall caused by the clipping and defacing of coins.

The basic principle of taxation is to impose a duty on something we cannot live without, in this case light and air. In 1696, a window tax was introduced — based on the number of windows in a property worth over £5 a year — and this was augmented on six separate occasions between 1747 and 1851, at which point the tax was finally abolished. Over this 150–year period the ingenuity of Georgian speculators in sidestepping a variety of impositions was tested. Within the new law, at one point, a series of tax brackets existed, with thresholds at 10, 20, and 30 windows. The obvious trick in this case was to build with 9, 19, or 29 windows to avoid jumping up into a more expensive bracket. Groups of windows separated by only 12 inches (305 mm) counted as one window, which may have accounted for the popularity of the Venetian window, or Serliana [1] as it is also known, and in the weavers’ houses of the Pennines the long ranges of windows, with their structurally supporting millstone grit mullions could be taxed as one [2]. It is very probable that many window openings were blocked up during construction, with the intention of un–blocking them at some point in the future, following the hoped–for abolition of the window tax.

In existing houses the only solution was to take out the windows and brick up the opening [3], but there was a practical limit to this course of action. The innkeeper’s wife in Fielding’s Tom Jones, published in 1749, complains — “ It is a dreadful thing to pay as we do. Why now, there is above forty shillings for window lights, and yet we have stopt up all we could: we have almost blinded the house, I am sure”.

The terminology is not important: ‘blind’ window is the most commonly employed term, but ‘blank’, ‘bricked–up’, or ‘blocked’, will do just as well in most cases, indicating solidity as opposed to transparency [4,5]. There appears to be a widespread supposition that it was the window tax only that gave rise to blind windows, but this is not the case as we can see if we take a wider view. Historically, blind windows had occurred in Britain before the introduction of the tax for a number of reasons, some of which were practical, some aesthetic — the desire for uniformity within a façade — and others a combination of both; and of course the same applied throughout in Europe.

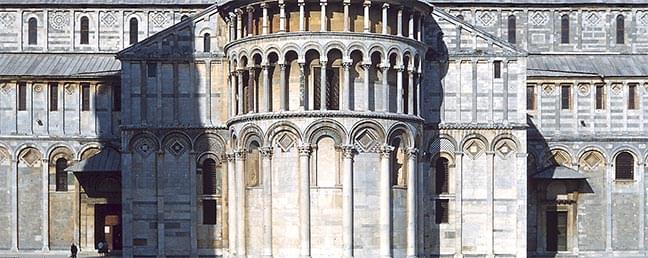

In Renaissance Italy, architects had introduced blind windows by way of articulating and enriching façades, together with other ways of varying the surface treatment of their buildings such as the blind arcade [6] and even the blind balustrade [7]. Fenestration, the arrangement of windows, regular or otherwise, could sometimes take precedence over the practical purpose of providing air and light. Early travellers to Italy, predominantly rich landowners and their retinues of architects and pictorial artists, brought back with them what we might call new ways of seeing, which were ultimately to become the foundation of Georgian style. Sixty years before the first King George came to the throne the author and architect Roger Pratt, returning from his travels to Rome in 1664–65, was writing about the ‘New Way of Architecture’. This style developed through the reigns of nine monarchs (the last four being Georges), subtly changing due to the influence of technological advances, shortages of materials and manpower during times of war, and new fashions; but the more it changed the more it stayed essentially the same. Eventually the blind window was to become a design element itself.

LOGGIA CORNARO, PADUA, ITALY, 1524

Designed by the architect Giovanni Maria Falconetto for a rich patron, Alvise Cornaro, this building [8] was created for the purpose of providing elegant entertainments. We have no record of the exact brief, but it is clear that for whatever reasons there was no intention to “over–light” the interior. The building is divided into five sections or bays, but only two of these five are given windows, the other three having blind windows; these, by way of emphasising the cultural nature of the edifice, are enriched with statues of Apollo, Diana, and Venus, figures from classical mythology. That the architect felt the need to provide these enrichments of the facade will be understood by comparing the finished building with an unembellished version [9].

The Loggia Cornaro and the adjacent Odeon (music rooms) can be visited by arrangement with the local tourist office.

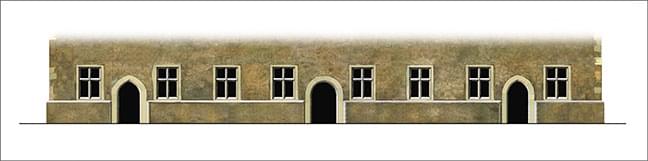

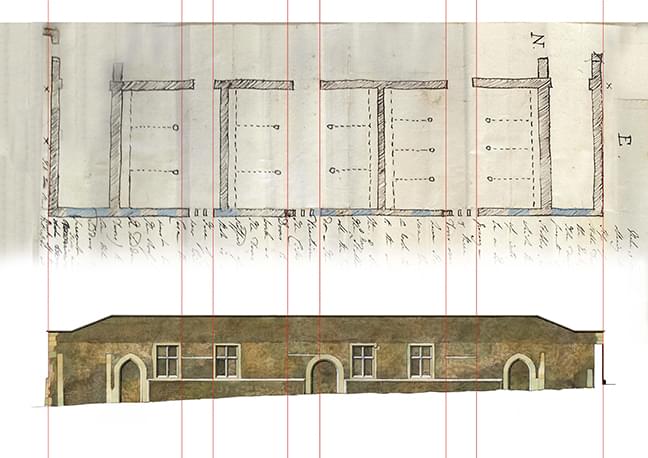

COLESHILL HOUSE, BERKSHIRE, 1662

At Coleshill, the site of a now demolished seventeenth century house by Inigo Jones/Roger Pratt, lies a part–built house in a forgotten wooded corner of the estate [10]. Windows and doors have been blocked up with stone, presenting a manifestly blind appearance. A conjectural reconstruction may be compared with a measured drawing of this frontage [11], and it will be seen that the intention seems to have been to provide three dwellings. It has been conjectured that these were part of a service wing associated with an earlier house that had been started and later abandoned. Whether it was ever occupied by domestic servants is not known, but it is clear from a surviving eighteenth century plan [12] that at one point the building was converted to stabling and cart storage, the interior being stripped out and remodelled with access for horses from the back. Light was provided by means of new windows on the frontage at a higher level, the cills of which are still visible in the structure; we may suppose that these windows were of timber, which would explain why they were swept away when a final remodelling as storage took place at an unknown date. The building now houses estate and garden implements.

10 [top] The Coleshill building as it appears today. 11 [middle] Tentative reconstruction of the

building as former dwellings; there are no clues as to whether the building was originally of one

or two storeys. The change in the character of the stonework at high level appears to be a consequence

of the stable conversion. 12 [bottom] Surviving eighteenth century plan showing conversion

to stables together with a measured drawing of the building as it stands now. Note the correlation

between the windows on the plan and the surviving stable conversion window cills seen on the drawing.

Coleshill house was gutted by fire in 1952 and subsequently pulled down; the estate is now administered by the National Trust.

WROXTON ABBEY, OXFORDSHIRE, 1680s

Nicholas Barbon, noted speculator after the Great Fire of London, and creator of many terraces of uniform well–proportioned late seventeenth century houses around Holborn, observed that:

. . . one might know by the visage of the citty houses in the chief street, of what calling the chief contriver was. As some being set out with fine brick–work rubb’d and gaged, were the issue of a master bricklayer; if stone coyned, jamb’d, and fascia’d, of a stone mason; if full of window . . . a glazier . . .

This was recorded by Roger North, a lawyer with whom Barbon had had some dealings, who was later to give up his practice for political reasons and retire into the country to apply himself to the study of architecture — ‘the flower and crown . . . of all the sciences mathematical’. He was always happy to share his findings with anyone who cared to listen, and was particularly critical of the gentry and nobility who, in their country houses ‘cannot depart from the citty way of compacting rooms into as little wall as possible; and punching the walls full of windows like pidgeon holes’. He says that:

. . . a small or ordinary room should not allow above 4 foot to the windows [i.e. in width]. I know it is an error, to affect much light, and wee confess it, by darkening o’lights againe with curtains . . . This mistake of over lighting an house, came in upon the reforme of building in Europe after the Gothick arrived at its utmost refinement. The castle–manner used in those countrys in elder time . . . used very small windoes . . . Peace and plenty made for luxury in building as well as other things, and then they left the castle manner, and fell into a contrary extream, of making a house like a bird cage, all windoe. The French buildings were so, and wee followed, and, as in other foolerys, out–did them.

It should not surprise us to learn that Roger North offered this advice to his brother Francis, Lord Keeper North, who was at that time making alterations to his Jacobean house at Wroxton Abbey, in Oxfordshire. This house, North says — ‘ had great roomes caged by windoing; and being to be finished up, I urged very much, to have above half the lights stopt up, and it made the rooms exceedingly better, and if I had had my will, more had been served so’. It seems likely from this comment that The Lord Keeper may have put up some resistance; this must be one of the few historical examples of windows being blocked up due to the intervention of a relative.

The house, with windows returned in Victorian times to the original stone mullioned Jacobean pattern, is now the English campus of the American Fairleigh Dickinson University.

BOUGHTON HOUSE STABLE BLOCK, NORTHAMPTONSHIRE, 1705

Ralph, Duke of Montagu, remodelled his house during the 1680s and the 1690s, completing the stable block in 1705. Given the character of the house itself and the size, number, and extent of the windows [13] it seems unlikely that he would have felt the need to concern himself unduly about the window tax, so we may reasonably assume that the blind windows adorning the flank wall of an adjunct [14] of the stable block are more or less as originally planned — though this cannot be determined without time–consuming and possibly fruitless documentary research. What is interesting for our purposes is that one of the upper floor windows, apparently originally ‘blind’ brickwork (unless the existence of the cill tells us otherwise), has been painted black and overlaid with a pattern of timbers in exact imitation of the adjacent windows, a subject which is discussed in Note 5, while on the ground floor two of the originally square blind windows have been opened up and real glazing inserted into the apertures. The evidence for this lies firstly in the red brick dressings of the jambs, which indicate the original height of the (blocked) opening, and secondly in the obvious new pointing of the brickwork where the opening has been extended downwards without red dressings.

13 [left] A corner of Boughton House. 14 [right] Flank wall of the building attached

to the stable block at Boughton, showing modifications to blind windows.

As with most blind windows of this period the inset brickwork is set back by 30–50 cm, that is to say roughly in the same plane as the glass of a window. Interestingly this increases to 100–115 mm in the period following the Act of Parliament of 1774 that caused the box frame to be set back behind the jambs and therefore by at least half a brick. Also of interest is that the coursing of the brickwork is maintained here, whereas in other examples it is not, indicating that forming the window aperture and filling it in are two separate procedures — in some cases signifying that the infill was later, or alternatively that it was a temporary solution to the problem of the window tax.

Boughton House is the home of the Duke of Buccleuch and is occasionally open to the public for guided tours at specified times.

QUEEN ANNE’S GATE, WESTMINSTER, LONDON, 1705–6

These houses [15, 16], occupied from 1705 onwards, are the best of their kind in London. Although very badly treated in some cases by later owners, most have been sensitively restored to something like their original condition. One exception is in the thickness of the glazing bars, which have been replaced piecemeal over the centuries with inappropriately thin bars — the development of the sash window was in its infancy in 1705 and glazing bars could be up to 50 mm thick at this stage. The windows are set flush and the recessed blind windows [17], including the half–width blind windows [18], are correspondingly shallow, as at the Boughton House Stable Block. What sets this group apart from others of the same period is the quality of the detailing, the stone bands marking the storeys, the carved stone grotesque keystones, and the elaborate wooden door heads.

15 [top left] Queen Anne’s Gate, looking west. 16 [top right] Queen Anne’s Gate, looking

east. 17 [bottom left] Full–width blind windows. 18 [bottom right] Half–width blind window.

The half–width blind windows do not, as one might think, correspond with the party wall, but sit a little to one side; this can be seen clearly where chimneybreasts sit back–to–back on a party wall [19]. Andrew Byrne, in London’s Georgian Houses, has suggested that this has something to do with avoiding draughts near the fireplaces of the front rooms, the introduction of a blind window as a feature on the frontage tending to push the windows away from the party wall. Unlike the blind windows at Boughton House Stable Block the coursing of the infill brickwork here does not match the general coursing; the reason for this is not known, but it indicates that the procedure at Queen Anne’s Gate was to create an opening that would then be filled in, rather than to bond in the recessed panel brickwork as the wall rose. This in turn suggests that the methodology might possibly be an eighteenth century exercise in keeping options open.

19 The party wall lies midway between the half–width blind windows. There is a strong

suggestion, based on the apparently ‘new’ brickwork to the left of the party wall, that

these windows may have been sashed at some time in the past.

At the present day all the half–width blind windows in this group of houses appear to be as original; however, it is known from record drawings prepared in the last century for The Survey of London, that in at least one house the ‘blind’ panel of brickwork had been demolished and a narrow sash installed (now removed and the opening bricked up again). The date is not known but it would seem more likely that this window would have been fitted following the removal of the window tax in 1851. There is also evidence in the brickwork itself that opening–up had taken place at some relatively recent period, then filled in later.

CHISWICK VILLA ‘LINK’ BUILDING, HOUNSLOW, 1730

When Richard Boyle, third Earl of Burlington and amateur architect, built his neo–Palladian house at Chiswick [20] between 1726 and 1729 he sited it near his Jacobean house; three years later he felt the need to link the two together so that family and guests could move between the two under cover, and found himself in the same predicament as G M Falconetto at the Loggia Cornaro, Padua. The link building between the old and the new houses was effectively a first floor corridor, comparatively narrow and therefore easily lit by a limited number of windows. The south east façade [21], facing the direction of main entrance to the house, was furnished with three first floor windows, adequate for lighting and ventilation purposes, together with niches to break up the expanse of stonework. The other side needed only one window to provide cross ventilation and the obvious central location was chosen as can be seen in the computer modified photograph [22]. The Earl’s desire to break up the mass of stonework visually led him to adopt the inevitable solution, the introduction of blind windows following the exact pattern of the south east façade [23].

20 [top left] Chiswick House, northwest front. 21 [top right] The Link Building seen from

the southeast. 22 [bottom left] Computer–modified view of the northwest front of the

Link Building. 23 [bottom right] The same view in reality.

Chiswick House is maintained by English Heritage.

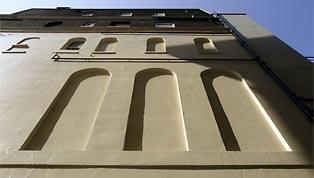

THE NINETEENTH CENTURY

The ‘Queen Anne’ window, in which the sash box sat forward in the window opening almost flush with the face of the brickwork, had gone out of fashion at the end of the eighteenth century following the 1774 Building Act already mentioned, so that by the nineteenth century windows were set back by half a brick, 100–115 mm, and blind windows followed suit [24 – 27]. As in earlier times a brick arch or a wood or stone cill, or other enrichments, might be incorporated purely for the sake of consistency with the detailing elsewhere on the façade.

24 [top left] Typical treatment of the flank wall of a terrace — for the purposes of visual relief.

25 [top right] Tall semicircular–headed blind windows alleviate the tedium of a blank wall.

26 [bottom left] Dulwich Picture Gallery: blind windows within a blind arcade – a device to

break up the vast expanse of wall enclosing this top–lit gallery. 27 [bottom right] Architraves

add definition to the blind windows in flank wall of these grand terrace houses in West London,

presumably echoing decorative elements on the main façade. Unusually, windows appear at

roof level, presumably to compensate for the inadequacies of dormer lighting.

Because the window tax was not repealed until 1851 it follows that only in the first half of the nineteenth century are we likely to encounter blind windows that have come into being solely on account of the tax; identification is difficult, but where the coursing carries through and brick recessed panel is bonded in to the brick of the walling, and the date of the building is known to be pre–1851, we can be sure that the blind window was meant to be permanent, and not intended to be modified later.

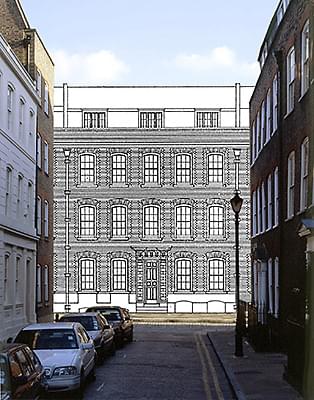

SPITALFIELDS, LONDON, 1996

In considering initial proposals for an extensive development by a major volume house–builder in the sensitive Conservation Area of Spitalfields, London, a decision was taken by English Heritage, supported by local amenity groups, that the new work should replicate the Early Georgian fronts of the houses that had been built on the site in 1725. These, built by Jonathon Beaumont, a mason, had been in continuous use up until their demolition in 1961. Early photographs were used together with record drawings that had been prepared by The Survey of London (English Heritage’s Research Department) before demolition had taken place, to reproduce the façade as accurately as possible. One of these detailed record drawings can be seen in [28] superimposed on a photographic view down an adjacent street. In the finished development [29] it will be seen that this frontage has been faithfully reproduced in almost all its particulars. However, due to the exigencies of internal planning it was necessary to introduce a row of blind windows at the upper levels in order to conceal a dividing party wall. In another quarter of the development [30], replicating local houses of the Late Georgian Period, it will be seen that the ‘blind window’ concealing the party wall is treated as a continuous vertical feature.

28 [top left] Spitalfields; The Survey of London drawing superimposed on the street scene.

29 [top right] The finished building, showing blind windows on the central ‘party wall line’,

in place of the actual sashes seen on the drawing in this location. 30[bottom] Another phase

of the same development, incorporating vertically elongated blind windows.

VENICE, 2011

The temporary blinding of openings for security purposes during building work is common. What is not so usual is the sensible provision of small squares of glass coupled with air brick to provide through ventilation, as seen in the restoration of the Convento dei Crociferi in Venice [31], in order to reduce the probability of rot and infestation.

THE LAST WORD

Window tax or not window tax? Andrew Byrne, in London’s Georgian Houses, remarks that:

. . . the result in London is not easy to isolate. Often a blank window was purposely placed within an elevation to maintain symmetry and rhythm as, for example, on a party wall line. Today only a small amount of houses retains those blank windows which can definitely be attributed to the tax. The fact that, in spite of the vast increase in building the number of taxable houses in London was smaller on 1800 than in 1750, suggests that the many new and existing houses had their windows blocked up and, by implication, that on its repeal in 1851, many brick panels returned to being windows.

Experts do not always agree, and by contrast we have Alec Clifton–Taylor stating in The Pattern of English Building that ‘Blocked windows, sometimes with simulated painting, are still to be seen on Georgian houses throughout the country; and although it would be a mistake to attribute all these to the window tax, the large majority are certainly due to it.’ . . . And what of the painted false window [32]? What does this tell us? Now move on to Note 5 . . .

Acknowledgements

All photographs and drawings are by the author.