ST PATRICK’S WELL 1527

Visitors to the fortified city of Orvieto in south–western Umbria, Italy, built on an outcrop of volcanic tufa, have the opportunity to experience the Pozzo di San Patrizio [1–5] — St Patrick’s Well — a descent down a 13m diameter spiral ramp to the water level 55m below — crossing a narrow bridge suspended above the water level — and a climb back up on an intertwining spiral ramp, the route being lit by means of 70 large window openings. Why St Patrick’s Well? The usual explanation offered is based on its supposed likeness to the well of the same name in Ireland, also known as St Patrick’s Purgatory, a well or pit in an island on Lough Derg, County Donegal, still a place of pilgrimage and retreat, in which the fifth century Saint is said to have spent some considerable time, and which was thought by the superstitious to be the entrance to Hell. We are told that this location was widely known in Europe from the twelfth century onwards, appearing as it did on maps of that period, and it would certainly have been known by the Church in sixteenth century Italy, as being yet another manifestation of the troglodytic inclinations of the early Holy Men. The Orvieto structure is however also known by the secular and comparatively self–explanatory name — Il Pozzo della Rocca, the Well of the Fortress. (It is worth mentioning that the Italian word pozzo is derived from the Latin puteus, meaning a pit or a well, which in turn gave us our own word pit).

The question arises — ‘how did this unusual structure come about?’ The story starts in 1527 with Pope Clement VII [6] finding himself quite seriously incommoded by the mutinous troops of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (a loose European political entity which, as Voltaire remarked was neither holy, Roman, nor an empire), and being forced to flee to the safety of the Castel Sant’Angelo, thereby avoiding a series of events which afterwards came to be spoken of as The Sack of Rome [7]. Escaping after six months, dressed as a beggar, or as a laundress according to another account, he took refuge in the fortified papal state city of Orvieto, and prepared to be besieged. In order to ensure a plentiful supply of water in the event of a siege Clement VII employed the services of the architect/engineer Antonio da Sangallo the Younger, one of a large and talented family, who was by then, at the age of only 36, chief architect of St Peter’s Basilica in Rome. More particularly he had been involved in 1525 in hydrological investigations in Orvieto to confirm the presence of springs.

6. [ left ] Pope Clement VII, as painted by Sebastiano del Piombo,1531. 7. [ right ] The Sack of

Rome, with the Castel Sant’Angelo in the far distance.

With his background and military engineering connections Sangallo may well have been aware of twelfth century Well of Saladin (or of Joseph or Yusuf) at Cairo, which legend has it was created by Crusade prisoners, and which was also built in order to ensure Cairo’s safety in the event of siege. Modern accounts of this well differ in detail but suggest that it consisted of two rectangular shafts offset from each other, excavated out of the rock to a depth of about 90m, with a chamber at about the mid–point incorporating a water tank. A pair of oxen, permanently located here, turned a wheel which operated a chain of pots bringing water up to this tank, from where another pair of oxen working in the same way at ground level brought the water to the surface. Access to the bottom of the well is described by one author as ‘a stairway of 300 steps, whence the name Well of the Spiral’, and by another, Mrs R. L. Devonshire, Rambles in Cairo, 1917, as ‘a simple incline’; the modern tourist web site TOUR EGYPT declares that ‘a spiral staircase with observation windows winds around the exterior of the well’.

DOUBLE SPIRAL (or Double Helix, to be precise)

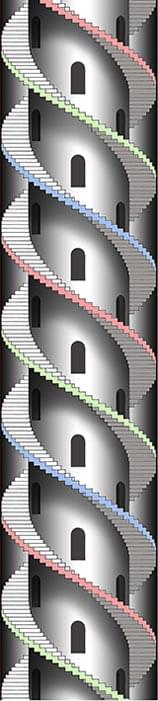

There appears to be no suggestion however of an intertwining double spiral in the Cairo well, which might lead us to conclude that Sangallo came up with this bright idea for his well, if it were not for the fact that double spiral staircases existed at that time in Italy, France and Germany, and in the narrow shafts of the minarets of market buildings and mosques in what is now Iraq. Furthermore François I, king of France, had started five years earlier to build himself a Château at Chambord which contained a double helical staircase [8–11] around a windowed masonry drum or shaft located at the centre of the main body of the building and therefore requiring top light — effectively a well ‘sunk’ into the structure. Two years earlier François I had invited Leonardo da Vinci to leave Italy and live in France permanently. This has given rise to the legend that Leonardo designed the Château de Chambord, largely on the basis of his sketches in his notebooks of double and quadruple spiral staircases — but there appears to be no firm documentary evidence for this assumption.

8. [ top left ] The double spiral staircase at Château Chambord, France. 9. [ top right ] View

inside the staircase, winding around the central shaft. 10. [ bottom left ] View inside the shaft,

looking across to the trapezoidal windows, the heads and cills of which follow the slope of the stair.

11. [ bottom right ] Looking up from ground floor level; the ‘top light’ is now provided by a

powerful electric lamp.

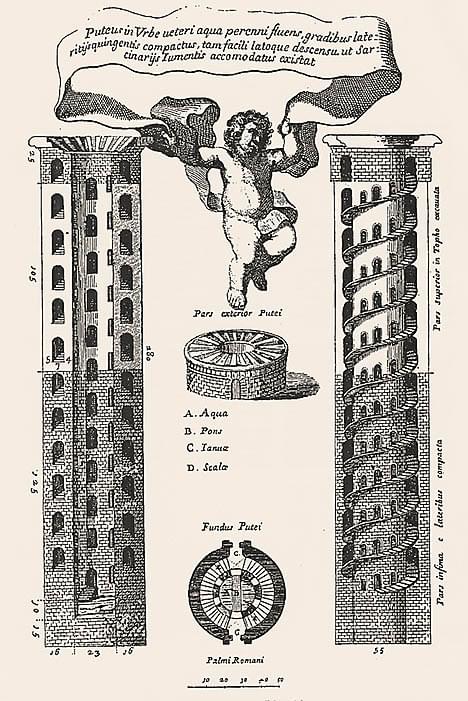

Was Sangallo aware of these jottings? Perhaps not — whatever the case his solution to the Pope’s problem seems to have been an amalgam of built precedent, ingenuity (ingegnere = engineer), and urgent necessity — a double spiral around a circular brick core pierced with openings for light and ventilation, the steps being supported by the central core and the outer masonry shell of the shaft. Mules, asses, or donkeys would descend 55m to the level of the water carrying panniers on their backs, by means of a form of staircase common in Italy — the scala cordonata or ramped stair [12], commonly used in urban areas where horses were stabled at an upper level. At the bottom, having presumably been loaded up by human intervention, they would cross a bridge over the water [13–14] and climb up to ground level by the other ramped stair, thus avoiding the need for two pack animals to pass each other. The principle is still in use today in modern railway tunnel emergency escape shafts — escaping passengers climb one staircase while the fire fighters descend by an intertwining stair within the same shaft.

12. [ top left ] The mule–friendly ramped stairs of the Pozzo di San Patrizio. 13. [ top

right ] The two spiral ramps are joined together by this bridge just above the water level,

from which the mules were loaded up with their consignments. 14. [ bottom right ]

Another view of the bridge. 15. [ bottom left ] Italian Health & Safety warning at the

entrance to the Pozzo.

The 13m diameter of the Pozzo shaft and the corresponding dimensions of the inner core, together with the 70 windows, allow a reasonable level of daylight to reach the spiral ramps, especially as the time taken to make the full descent allows the eyes to compensate for the diminishing light level. The modern visitor is advised not to throw objects from the windows [15], the word used being finestroni — literally big finestri — windows. (The suffix –one indicates ‘big’ as in the Italian sala a room, salone a big room — English ‘saloon’). This exhortation is, naturally, ignored — as the coins in the floor of the well bear witness.

Excavation of the Pozzo shaft started in 1527, the same year as the Sack of Rome — quick work by Sangallo and his builder Giambattista da Cortona. As if Pope Clement didn’t have enough to think about around this time this was also the year that Henry VIII started troubling him for an annulment of his marriage to Catharine of Aragon. Work was finally finished in 1537, by which time Clement VII had come to terms with Charles V. The siege never happened.

(The annulment did; but without the Pope’s approval — it cannot have helped Henry’s case that he was married to the aunt of The Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V. The resulting events changed the face of Britain irrevocably).

ANOTHER MILITARY HOLE IN THE GROUND

England declared war on France in 1803. Military fortifications at the Western Heights at Dover had been in built with a view to defending the town from landward attack in the case of invasion, but the renewed threat of a landing by Napoleon’s army brought about a resolution to improve the sea defences. The sea was 55m below the barracks at the Western Heights and accessible by a march of some distance. There was a need to get troops down to the bottom of the cliff as quickly as possible in the case of an attack from that direction. A radical solution was proposed by Brigadier General Twiss, in a letter dated October 1804 to the Inspector–General of Fortifications:

Sir,

The new barracks for a Battalion of 750 Men and Officers now erecting by the Barrack Office, near the Drop on the Western Heights at Dover, are situated little more than 300 yards horizontally from the Sea Beach, before the Town, and about 180 feet above high–water mark, but in order to communicate with them from the center of the Town, on Horseback, the distance is nearly a mile and half, and to walk it about three quarters of a mile, and all the Roads, unavoidably pass over Ground more than 100 feet above the barracks, besides the Footpaths are so steep and chalky, that a number of accidents will unavoidably happen, during the Wet Weather, and more especially after Frosts. ~~~ I am therefore induced to recommend the construction of a Shaft, with a Triple Stair Case, as shown in the Plan and Estimate transmitted herewith, the chief Object of which is the convenience and Safety of Troops, but I conceive it will also be highly advantageous in case of a an attack, by opening the shortest and securest communication with the Town, and may eventually be useful in sending reinforcements to Troops employed in Defence of the Beach or the Town, or in affording them a secure retreat.

Wm Twiss

Diaries and letters of any period give us insights into the events of history that would otherwise pass us by, and personal observations can bring the past into focus in a way that straightforward histories cannot, sometimes linking an event to some unexpected curiosities. As for instance in the letters of the celebrated Hester Lynch Piozzi (formerly Mrs Thrale, close confidante of the renowned Dr Samuel Johnson, before she married an Italian) where we hear the effects of the French Revolutionary Wars, and the threat of a Napoleonic invasion on the people of Britain, as they happen. A thread of fear runs through her letters to her friend Mrs. Pennington — "the Nation, the Continent, the world itself seems in its last convulsions . . . Can too many efforts be made to keep these marauders out, these pests of Society, who have shaken such a fabric to its foundations?" — although a little later in the same letter she notes complacently "The weather however is charming". Elsewhere she records the attitude to the threat of invasion by John Joseph Merlin, whom she christened ‘the Fool’ — a Belgian inventor living in England (supposed creator in 1760 of the first rollerblades which he attempted to demonstrate while playing the violin at the same time, and smashing a mirror worth £500). Although comparatively sane much of the time, he is recorded by Hester Piozzi as remarking — on the subject of repelling the French army of invasion — "Could they not stop them at the Turnpikes?"

THE GRAND SHAFT 1804

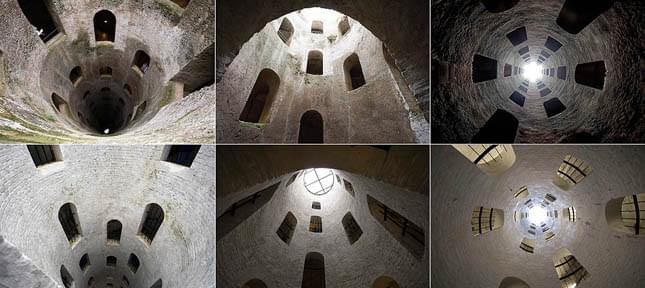

16. [ top left ] View looking down the Grand Shaft, Dover. 17. [ top right ] The view looking

up from about mid–way. 18. [ bottom ] The view directly up from ground level.

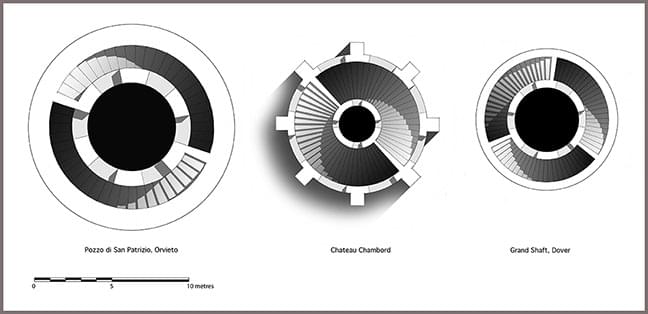

After some disagreement on minor matters with a fellow member of the Committee of Engineers — ‘A shell falling in the shaft might destroy its use’ — Twiss won his staircase, The Grand Shaft, and work started in 1804, taking three years and costing a fraction over £3,221, more than £700 below the original estimate [16–18]. The startling resemblance to the Pozzo di San Patrizio will be immediately apparent — the circular shape of the shaft and the inner brick core with its windows providing light and ventilation; the only noteworthy differences are the dimensions, the triple stairs, and the fact that whereas the stairs in The Grand Shaft spiral downwards in an anti–clockwise direction [19] those at the Pozzo spiral downwards in a clockwise direction [20–21]. It is worth noting that The Grand Shaft was designed to allow for two men abreast on each staircase, in other words a ‘front’ of six men, which Twiss’s antagonistic fellow officer had thought less efficient than a road down to the sea that could cope with a front of twice that number, forgetting that time was also part of the equation.

19. [ top left ] Drawing of the triple stair of the Grand Shaft; the colours identify the three concentric

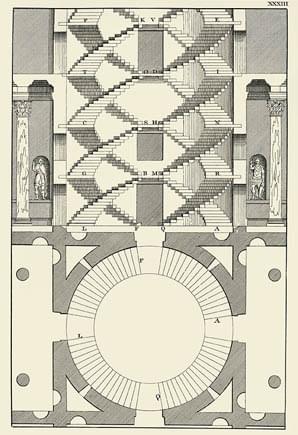

helical stairs (‘spirals’ for short). 20. [ top right] An engraving from a seventeenth century

description of the Pozzo di San Patrizio by Filippo Buonanni. 21. [ bottom ] Comparative plans of

the stairs at the Pozzo, Château Chambord, and the Grand Shaft. The drawing is based on material

from a variety of sources and does not pretend to be an accurate measured survey.

The Grand Shaft is the smaller of the two shafts, the outer diameter being 8m as opposed to 13m (Pozzo), the depth 42m as against 55m (Pozzo), and with an estimated 40 windows as opposed to 70 (Pozzo). The number of steps cannot be compared as the Grand Shaft has regular treads and risers [22], whereas the Pozzo has mule–friendly ramped steps. Access to the Grand Shaft is by way of a long straight flight down from the parade ground and a double sweep curving round the shaft itself [23, 24]. At the base of the shaft a tunnel leads to the harbour, beach and town. By contrast, the Pozzo has a simple circular drum at its head. Both shafts are open to the sky, each with a modern mesh covering for safety reasons and to exclude birds. The Grand Shaft is now listed Grade II.

22. [ top ] View down one of the three staircases of the Grand Shaft. 23. [ bottom left ]

The straight flight approach to the Grand Shaft from the level of the barracks at the top of the cliff.

24. [ bottom right ] The mesh–covered top of the shaft and the double sweep staircase

leading to it, about to be tested by a small army of architectural historians.

Would not each of these shafts have been better lit if the ramps and stairs had been more open? This would have been a structural possibility even in the sixteenth century [25]. The stairs of the Grand Shaft might have been supported easily by cast iron columns with raking curved cast iron strings supporting the treads, rather than stone, iron having been forged and cast in the Weald of Kent for many centuries. The answer must be that both shafts were strictly utilitarian structures, needed quickly and therefore constructed in the most readily available and inexpensive materials, and that the window openings, though they could have been larger, provided lighting and ventilation levels sufficient for the purpose.

It is hard to believe that Brigadier General Twiss had not had foreknowledge of the Pozzo di San Patrizio before coming up with his ingenious solution, yet details of his career do not reveal any visits to France or Italy. As an experienced military engineer he might have had access to details of foreign military defensive works, and heard or seen reports of Sangallo’s work in Orvieto and elsewhere in Italy. It would be interesting to know whether or not he had come across a copy of a two–volume publication by the Jesuit Filippo Buonanni, Numismata Pontificum Romanorum (1699), which illustrated details of the Pozzo [20].

25. [ left ] A spiral stair supported on columns at the Villa Madama, Rome. Although this is an early

twentieth century addition to the Villa (started by Raphael 1518 and later supervised by Sangallo the

Younger) it is very much in the style of the sixteenth century. 26. [ right ] Palladio’s mistaken idea

of the spiral stair at Château Chambord.

Or it is possible that Twiss was familiar with Palladio’s Four Books of Architecture, written in 1570? On the subject of staircase lighting he had written:

— ‘ they succeed very well that are void in the middle, because they can have the light from above, and those that are at the top of the stairs, see all that come up, or begin to ascend, and are likewise seen by them . . .

And in his First Book he illustrates a quadruple spiral stair [26] of which he writes:

Another beautiful sort of winding stairs was made at Chambord, (a place in France) by order of the magnanimous King FRANCIS, in a palace by him erected in a wood, and is in this manner: there are four stair–cases, which have four entrances, that is, one each, and ascend the one over the other in such a manner, that being made in the middle of the fabrick, they can serve to four apartments, without that the inhabitants of the one go down the stair–case of the other, and being open in the middle, all see one another going up and down, without giving one another the least inconvenience: and because it is a new and beautiful invention I have inserted it, and marked the stair–cases with letters in the plan and elevation, that on may see where they begin, and how they go up.

This must have been written from hearsay as we know that the Chambord staircase is a double spiral, not a quadruple; it seems possible that Leonardo da Vinci’s supposed involvement there may have led Palladio to conflate the facts, as reported to him, with his memories of Leonardo’s sketches of quadruple staircases (if indeed he was aware of them).

CONCLUSION

Who copied or was inspired by whom? Leonardo da Vinci had sketched double and quadruple spiral staircases in his notebooks in or around 1487. Antonio da Sangallo the Elder met Leonardo soon after this. Did he see the notebooks and discuss staircases with him? If so were these ideas passed on to his son, Sangallo the Younger? Or were such ideas common currency then, bearing in mind the existence of tenth century minarets with double spiral stairs?

Leonardo da Vinci went to Amboise in 1516 at the invitation of François I. There he encountered Domenico da Cortona, who was engaged in making a model of the proposed Château at Chambord for the King. Domenico da Cortona was a pupil of Giuliano da Sangallo, brother of Antonio da Sangallo the Elder and therefore uncle of Sangallo the Younger, who by 1520 was involved in creating the Pozzo, with its double spirals. Sangallo must have known da Cortona, one would think. Did Cortona’s model include a double spiral stair, or did that come later? And if so, at whose instigation?

27. A comparison between the Pozzo di San Patrizio (top row) and the Grand Shaft at Dover

(bottom row). Any further commentary would be superfluous.

Palladio wrote about Chambord in 1570, but what details had reached his ears? Work on the main body of the building had been finished by 1547 so that travelers’ accounts would have been based on the finished article rather than drawings or models, so why is his own drawing so completely at variance with the reality? Then there is a gap of over 200 years, and in 1804 we find Brigadier William Twiss proposing The Grand Shaft, a unique piece of military engineering bearing a very remarkable resemblance to Sangallo’s work in Orvieto [27] . How could this be? It is unlikely that we will ever know the answers to this and related questions, which can only be found by digging deep into the records of the past; the best endeavours of respected scholars have, regrettably, so far revealed no firm conclusions.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Dr Richard Morrice for his input and advice.

(All photographs and drawings are by the author unless indicated otherwise)

Picture 1: © Robert Helms

Pictures 6 & 7: Wikipedia PD